Support 100% Independent Research With Our 7-Day Free Trial

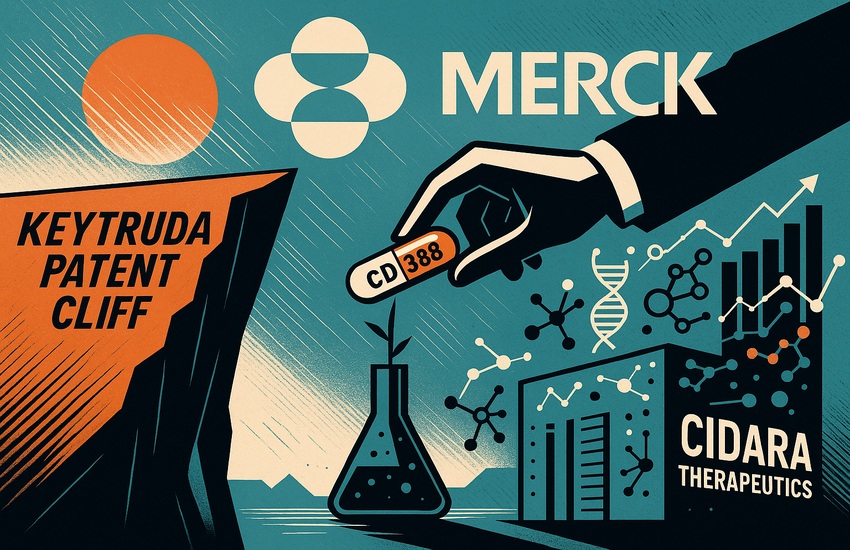

Merck isn’t waiting around for Keytruda’s patent clock to run out. On November 14, the pharma giant announced its plan to acquire Cidara Therapeutics for $221.50 per share in cash—valuing the biotech at $9.2 billion. That’s a 109% premium over the prior close and nearly 1,000% above where Cidara’s stock traded just five months ago. The Merck Cidara acquisition centers around CD388, a promising flu-prevention drug currently in Phase 3 trials. A single drug: CD388, Cidara’s long-acting flu prevention therapy that isn’t a vaccine and doesn’t rely on the body’s immune response. With Keytruda’s U.S. exclusivity set to expire in 2028 and a pipeline of new launches still ramping, Merck is racing to plug an $18 billion revenue hole. The move also comes amid a broader land grab in biotech, with names like Pfizer and Novo Nordisk also paying up for promising assets. For Merck, Cidara represents both a near-term growth lever and a long-term hedge against an increasingly uncertain oncology landscape.

The Keytruda Cliff Is Getting Closer

If you’ve followed Merck even loosely, you know the company has a Keytruda problem. The cancer drug accounted for 46% of Merck’s 2024 revenue and is projected to peak at $40 billion in annual sales by 2028. That’s the same year its U.S. patents expire, opening the door to biosimilar competition. Even though international patents extend to 2031–33 and a new subcutaneous version could offer protection until 2039, the looming cliff is real—and it’s steep.

Merck’s top brass has been anything but shy about the challenge. CEO Rob Davis has repeatedly emphasized the urgency to diversify, telling investors the company is focused on “science-driven, value-enhancing” deals to shore up the pipeline. The $10 billion acquisition of Verona Pharma (pulmonary diseases) in July and the earlier Acceleron buyout (Winrevair) in 2021 show Merck’s appetite for bolt-on deals with high clinical differentiation.

But unlike those previous deals, Cidara is about front-loading growth before 2028. Analysts expect CD388 could generate $3.5 billion or more in annual sales by 2035. That might not completely backfill the Keytruda hole, but it does offer meaningful revenue in the 2028–30 danger zone. With roughly 80 Phase III trials underway, Merck is counting on its pipeline—but it’s also keenly aware that pipeline success is far from guaranteed.

CD388: A Flu Drug That Could Be a Blockbuster

So what makes CD388 so special? In short, it’s a long-acting flu prevention therapy that doesn’t depend on a person’s immune system to work. That’s a huge deal for people who are elderly, immunocompromised, or vaccine-hesitant—groups that standard flu vaccines often fail to protect adequately.

Unlike a vaccine, CD388 combines zanamivir, a known antiviral, with an antibody fragment that sticks around in the body for months. In a Phase 2b trial, a single dose reduced flu infections by 76.1% in the highest dose group over 24 weeks. For context, last year’s flu vaccine was only 56% effective, and that was considered a good year. CD388’s performance was described as “game-changing” by analysts, and a Phase 3 trial is already underway.

Merck is betting big that CD388 can capture meaningful share from both vaccines and antivirals. The company’s own CEO, Rob Davis, called it “an important driver of growth through the next decade.” In an era when respiratory disease prevention has become a national priority—and when vaccine fatigue is very much a thing—CD388 offers a compelling alternative.

And because it’s not a vaccine, the therapy may appeal to those skeptical of traditional flu shots. That opens up new demographics. The timing is also critical: the U.S. just had its worst flu season in 15 years, and demand for better options is rising. If CD388 can launch by 2028 as expected, it could start producing revenue just as Keytruda falls off the patent cliff.

Biotech M&A Is Heating Up—and Getting Expensive

Merck isn’t the only pharma giant on the hunt. Biotech M&A is back, and it’s suddenly a seller’s market. Pfizer recently paid $10 billion for Metsera, an obesity drug startup. Johnson & Johnson just shelled out $14 billion-plus for Intra-Cellular Therapies. The total value of global pharma deals has risen 31% year-to-date, according to Bloomberg.

What’s driving it? In part, it’s the same patent cliff Merck is facing. Many large drugmakers are staring down looming expirations and need fresh pipelines. But there’s also a macro angle: biotech valuations were crushed over the last two years, and now that the XBI (a key biotech ETF) is rallying—up 25% since September—companies are rushing to strike deals before prices rise further.

In that context, Merck’s Cidara deal is part of a broader wave, but the premium it paid (more than 100% over the previous close) raised eyebrows. Cantor’s analysts admitted the size was “larger than anticipated,” though they acknowledged it’s one of the better uses of Merck’s balance sheet.

With net leverage below 1x EBITDA and nearly $5 billion in planned share buybacks this year, Merck can afford to play offense. The question is whether these bets will pay off fast enough to cushion the Keytruda blow—and whether Merck will need to keep buying to stay competitive in oncology, cardiology, and beyond.

Long-Term Implications for Merck and the Flu Market

In the near term, CD388 gives Merck a shot at entering a new therapeutic category with blockbuster potential. It also strengthens Merck’s vaccine-adjacent portfolio, which already includes Capvaxive (pneumonia) and ENFLONSIA (RSV). That creates operational synergies in manufacturing, distribution, and payer negotiations—no small thing in a margin-sensitive business like vaccines.

Longer term, CD388 could reshape how we think about flu prevention. If the drug proves to be more effective and longer-lasting than current vaccines, especially for high-risk populations, it could shift demand away from seasonal shots and toward once-per-season therapeutics. Of course, reimbursement and resistance concerns remain. Will insurers pay for a new flu therapy at a high price point? And could the virus mutate around zanamivir over time?

For Merck, success would help validate its “string of pearls” M&A strategy—picking up targeted, de-risked assets rather than placing a single big bet. It would also signal that the company is building a post-Keytruda growth engine, one that spans oncology, immunology, cardiology, and now infectious disease.

But integration risk is real. And CD388 is still in Phase 3, with no guarantee of approval. If the drug stumbles—or doesn’t get payer traction—Merck could find itself short on growth just when it needs it most.

Final Thoughts: A Bold Bet with Measured Upside

Merck’s $9.2 billion acquisition of Cidara Therapeutics is a calculated move to patch a looming revenue gap from the 2028 Keytruda patent expiry. CD388 offers a promising new angle on flu prevention, one that could be both scientifically and commercially differentiated. It’s also a signal that Merck is willing to pay up—perhaps overpay—in a frothy biotech M&A environment where sellers have the upper hand.

The risks? CD388 isn’t approved yet, payer appetite is uncertain, and the therapy could face resistance issues over time. But with Keytruda dominating nearly half of Merck’s revenue, the company is under pressure to act—and fast.

Valuation-wise, Merck is trading at a trailing EV/EBITDA of 8.05x and a P/E of 12.3x—below its historical averages and arguably cheap given its late-stage pipeline. The company’s balance sheet is solid, dividend yield is 3.5%, and free cash flow yield is over 12%. That gives Merck room to keep playing offense, even if it means paying biotech-sized premiums.

In the end, Cidara is one tile in a much bigger mosaic. Whether it proves to be a gem or just grout remains to be seen.

Disclaimer: We do not hold any positions in the above stock(s). Read our full disclaimer here.